Brexit, Trump and 'post-truth': the science of how we become entrenched in our views

Kris De Meyer, King's College LondonFinally a new year is here after the most politically divisive 12 months in a very long time. In the UK, Brexit shattered dreams and friendships. In the US, the polarisation was already huge, but a bitter election campaign made the divisions even deeper. Political rhetoric doesn’t persuade evenly. It splits and polarises public opinion. ![]()

As a citizen, the growing divisions trouble me. As a neuroscientist, it intrigues me. How is it possible that people come to hold such widely different views of reality? And what can we do (if anything) to break out of the cycle of increasingly hostile feelings towards people who seem to be on “the other side” from us?

To understand how the psychology works, imagine Amy and Betsy, two Democrat supporters. At the start of the presidential primary season, neither of them has a strong preference. They both would like a female president, which draws them towards Hillary Clinton, but they also think that Bernie Sanders would be better at tackling economic inequality. After some initial pondering, Amy decides to support Clinton, while Betsy picks Sanders.

Their initial differences of opinion may have been fairly small, and their preferences weak, but a few months later, they have both become firmly convinced that their candidate is the right one. Their support goes further than words: Amy has started canvassing for Clinton, while Betsy writes articles supporting the Sanders campaign.

How did their positions shift so decidedly? Enter “cognitive dissonance”, a term coined in 1957 by Leon Festinger. It has become shorthand for the inconsistencies we perceive in other people’s views – but rarely in our own.

What people are less aware of is that dissonance drives opinion change. Festinger proposed that the inconsistencies we experience in our beliefs create an emotional discomfort that acts as a force to reduce the inconsistency, by changing our beliefs or adding new ones.

A choice can also create dissonance, especially if it involves a difficult trade off. Not choosing Sanders may generate dissonance for Amy because it clashes with her belief that it is important to tackle inequality, for example.

That choice and commitment to the chosen option leads to opinion change has been demonstrated in many experiments. In one recent study, people rated their chosen holiday destinations higher after than before making the choice. Amazingly, these changes were still in place three years later.

Almost 60 years of research and thousands of experiments have shown that dissonance most strongly operates when events impact our core beliefs, especially the beliefs we have about ourselves as smart, good and competent people.

Pyramid of choice

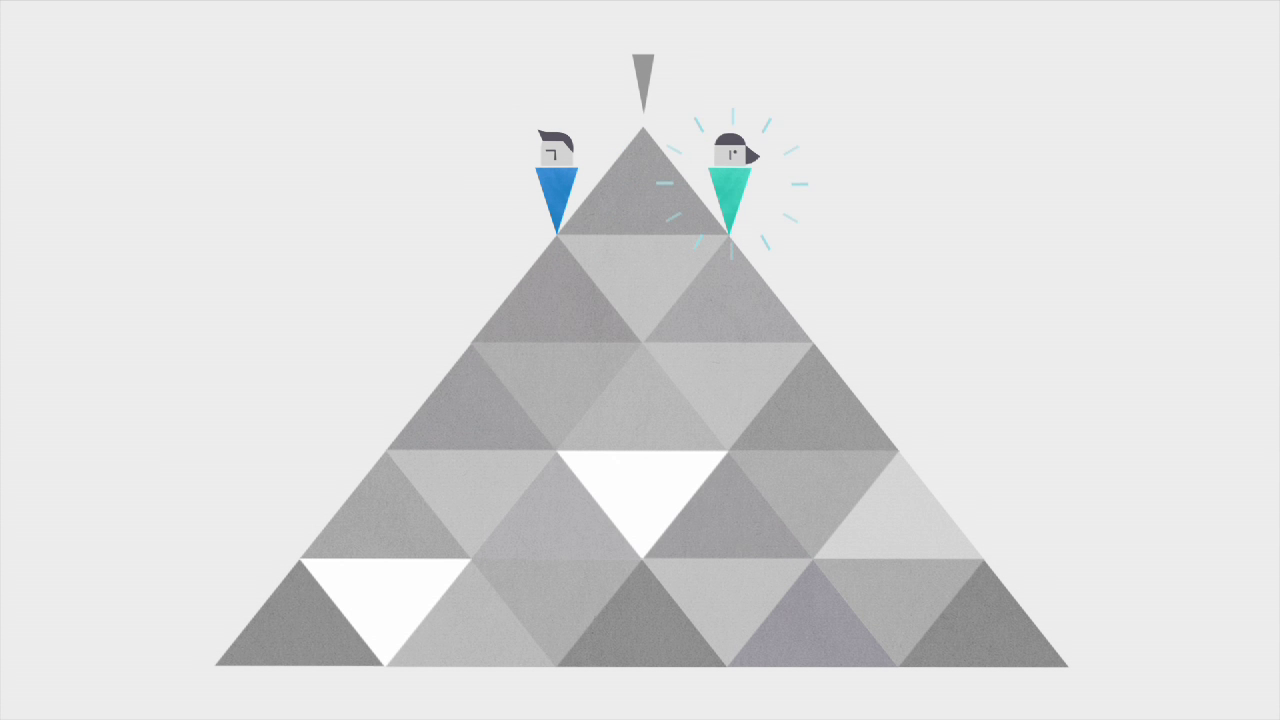

But how do we become so entrenched? Imagine Amy and Betsy at the top of a pyramid at the start of the campaign, where their preferences are fairly similar. Their initial decision amounts to a step off each side of the pyramid. This sets in motion a cycle of self-justification to reduce the dissonance (“I made the right choice because …”), further actions (defending their decision to family, posting to friends on Facebook, becoming a campaign volunteer), and further self-justification. As they go down their sides of the pyramid, justifying their initial choice, their convictions become stronger and their views grow further apart.

A similar hardening of views happened in Republicans who became either vocal Trump or #NeverTrump supporters, and in previously independent voters when they committed to Clinton or Trump. It also applied to Remain and Leave campaigners in the UK, although the choice they had to make was about an idea rather than a candidate.

As voters of all stripes descend down their sides of the pyramid, they tend to come to like their preferred candidate or view more, and build a stronger dislike of the opposing one. They also seek (and find) more reasons to support their decision. Paradoxically, this means that every time we argue about our position with others, we can become more certain that we are, in fact, right.

The view from the bottom of the pyramid

The further down we go, the more prone we become to confirmation bias and to believing scandal-driven, partisan and even fake news – the dislike we feel for the opposing side makes derogatory stories about them more believable.

In effect, the more certain we become of our own views, the more we feel a need to denigrate those who are on the other side of the pyramid. “I am a good and smart person, and I wouldn’t hold any wrong beliefs or commit any hurtful acts”, our reasoning goes. “If you proclaim the opposite of what I believe, then you must be misguided, ignorant, stupid, crazy, or evil.”

It is no coincidence that people on opposite ends of a polarised debate judge each other in similar terms. Our social brains predispose us to it. Six-month-old infants can already evaluate the behaviour of others, preferring “nice” over “nasty” and “similar” over “dissimilar”.

We also possess powerful, automatic cognitive processes to protect ourselves from being cheated. But our social reasoning is oversensitive and easily misfires. Social media makes matters worse because electronic communication makes it harder to correctly evaluate the perspective and intentions of others. It also makes us more verbally aggressive than we are in person, feeding our perception that those on the other side really are an abusive bunch.

The pyramid analogy is a useful tool to understand how people move from weak to strong convictions on a certain issue or candidate, and how our views can diverge from others who held a similar position in the past.

But having strong convictions is not necessarily a bad thing: after all, they also inspire our best actions.

What would help to reduce the growing antipathy and mistrust is to become more wary of our default stupid-crazy-evil reasoning, the derogatory explanations that we readily believe about people who disagree with us on matters close to our heart. If we keep in mind that – rather than being the “truth” – they can be the knee-jerk reaction of our social brains, we might pull ourselves just high enough up the slopes of the pyramid to find out where our disagreements really come from.

Kris De Meyer, Research Fellow in Neuroscience, King's College London

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed